Every economy has three potential sources of growth:

- An increase in the size of the labour force and/or more advanced job skills;

- Investment in more advanced manufacturing equipment;

- Innovation, or the creation of new products, using the existing labour force and manufacturing equipment.

For a number of years, ‘innovation’ has been the European Union’s new “mantra”. Latvia has fully adopted the idea of setting innovation programmes as the supreme goal of economic policy, as confirmed by the National Development Plan. As a result, insufficient attention has been paid to other means of encouraging growth, and in particular to one of the conditions most specifically important to Latvia, i.e. capital accumulation.

In the realm of global technology, the majority of Latvia’s enterprises are not considered to be direct competitors to American companies or those from other European Union member states.

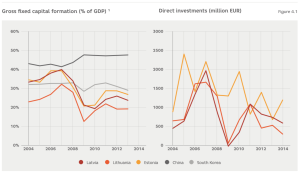

Instead, the challenge facing Latvian industry is to learn to produce products which more developed countries have invented and are already manufacturing, and to move further up the complexity ladder of such products. Investment in physical capital is a significant element of this process. Investment in Latvia reached a peak in 2007 and then fell sharply to 19% of GDP in 2010, before rising again to 25% of GDP in 2012. However, in 2013 and 2014, there was a significant reduction in the volume of investment. For the last three years, the volume of foreign direct investment has continued to fall.

4.1. Lending to enterprises

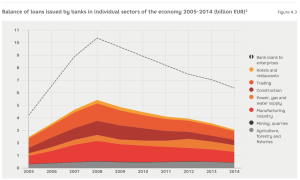

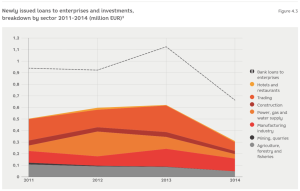

Overall trends, judged from the perspective of the banking system, show that, since 2008, there has been a significant reduction in the volume of loans issued (from EUR 21 billion at the end of 2008 to EUR 12.5 million in 2015). When it comes to the issue of loans to businesses, the trends are similar. During the past six years, the total volume of loans issued has gradually declined, which has a knock-on affect on the volume of investments.

In Figure 4.2, information is collated about the total volume of investments in Latvia, as well as the balances of bank loans issued to businesses. In the majority of the sectors reviewed, there has been a reduction in the volume of issued loans. The only exceptions to this trend worth mentioning are the power, gas and water supply sectors, in which the balance of issued loans has actually increased, compared with the corresponding level in 2007-2008, as well as the agriculture, forestry and fisheries sectors, where the volume of lending has remained quite stable during the past decade. With the exception of these sectors, we are left to conclude that lending trends are quite unfavourable.

The situation is contradictory. Banks have the financial resources, interest rates are at an all-time low, but banks’ loan portfolios are contracting.

Do enterprises not want to invest or do banks not want to lend?

4.2. Lending in Latvia

This study uses three instruments to study bank lending in Latvia. First, an exclusive data-set developed by Vjačeslavs Dombrovskis and colleagues at the Stockholm School of Economics in Riga’s TeliaSonera Institute between 2008-2011. This survey of innovative business in Latvia (SIBiL) tracks the development of over 1,200 small and medium-sized enterprises in the (SME) manufacturing sector from 2008 to 2015 . Secondly, in-depth interviews with board members of Latvia’s four biggest banks. Thirdly, case-study analysis of the experience of the timber industry.

SIBiL data

In order to understand the trends observed in Latvia since 2008, we studied enterprises grouped according to size and source of financing. The enterprises were divided into two categories according to the number of employees and into three categories according to their loan application/receipt status.

Conclusions

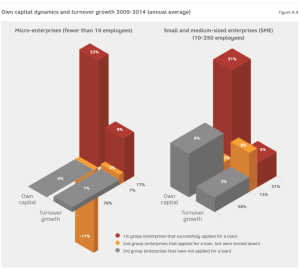

- Most micro-enterprises (63%) and SMEs (49%) do not apply for loans and are not interested in receiving bank loans3;

- The majority of enterprises (65% of micro-enterprises and 70% of SMEs) that applied for loans, did so successfully;

- Enterprises that had vailable credit rapidly increased their own capital;

- Enterprises that had available credit grew faster than enterprises that did not. From 2009 to 2014, the turnover of micro-enterprises grew by an average of 9% annually, while the turnover of SMEs rose by an average of 5% annually. By way of comparison – enterprises, which showed no interest in bank loans, reported a much smaller increase in turnover: in the case of micro-enterprises, only 1% annually, and in the case of SMEs, 3% annually.

Interviews with Latvia’s banks

During discussions with bank representatives, a range of broader problems which banks and businesses encounter were identified:

- Banks experience low demand for lending, largely because enterprises do not have sufficient capital to qualify for loans. Problems usually arise when an enterprise whose financial indicators have stabilised after the crisis, does not qualify for a loan, because the risk level is still negatively impacted by the drop in indicators during the crisis;

- Decisions regarding corporate loans are highly centralised and the assessment is made based on the financial data submitted and the company’s history. At least in relation to SMEs, the situation is rarely assessed on site, particularly in the regions. If an enterprise’s real situation differs from that depicted in official reports; e.g. if an enterprise avoids paying tax, this is not taken into account;

- At the same time, competition between banks for the business of Latvia’s 100 biggest companies is very high, which means that companies in this group enjoy easy and advantageous access to financial resources, compared with SMEs and micro-enterprises. The example of Latvijas Finieris, one of Latvia’s biggest and most successful enterprises illustrates this situation (see Case 4.1);

- Banks believe that their role in issuing loans to start commercial operations is quite small, because of problems in assessing risk and potential return on investment, therefore other sources of funding will continue to be more important in this segment;

- The large shadow economy that reduces enterprises’ legal cash flow, on the basis of which decisions are made about the issue or non-issue of loans;

- Problems related to insolvency proceedings, as well as the slow and complicated review of cases in courts increase lending risks and the real price of credit for enterprises.

The problem of the availability of credit mainly exists in relation to financing the investments of small and medium-sized enterprises. The main reasons are: the activities of enterprises related to the shadow economy (which reduces the credibility of financial data), the excessive likelihood of the non-repayment of debt obligations (using insolvency proceedings) and torturously slow and inefficient recovery of bad loans (slow review of cases in court).

There is little likelihood that significant and rapid progress will be made in the area of combating the shadow economy or in the legal realm. Therefore, the focus should be on solutions that can be implemented in practice during the next two years and which will improve the availability of funding for enterprises. We propose three courses of action.

Action 1

Use of reinvested profits by SMEs

The use of operating profits for investment can serve to improve the competitiveness of a business, thus enabling it to achieve better long-term results. At present, in Latvia, several corporate income tax incentives are in place that indirectly stimulate an improvement in the enterprise’s efficiency, but some of these are primarily geared towards bigger enterprises.

SMEs, and micro-enterprises in particular, have problems with access to financing. Evidently, the most frequently used source of financing is an enterprise’s own profits. The state can stimulate investment by not imposing corporate income tax (CIT) on profits reinvested by micro-enterprises and small and medium-sized enterprises.

In Estonia, this system has successfully operated for a decade and a half. The 2000 law is easy to understand and administer. Reinvested profits are subject to a 0% corporate income tax rate. After the introduction of the 0% rate, there has been a rapid increase in the amount of corporate income tax collected – rising from 0.72% of GDP in 2001 to 1.78% of GDP 2004.4 Waiving CIT on profits reinvested by small and medium-sized enterprises will improve access to bank loans, because enterprises will no longer be motivated to manipulate the declaration of profits, in order to avoid payment of taxes.

In Latvia, this problem is particularly relevant for small enterprises, due to the CIT advance calculation model. Declaration of profits will improve the quality and credibility of reports and thus improve access to bank loans. In Latvia, there is a belief that the current benefits to those enterprises, which invest in fixed assets, are sufficient to stimulate investments. A speeded-up system of writing off manufacturing equipment, using a ratio of 1.5 (this provision in the existing law is due to be in place until 2020), is already in place. However, this system helps those enterprises, which already have access to investment funding. An accelerated depreciation system does not reduce the motivation not to declare profits to avoid paying taxes.

Not taxing reinvested profits with corporate income tax could resolve the problem of limited access to investment financing faced by SMEs. The solution would be to apply this break to small and medium-sized enterprises, concurrently retaining the available corporate income tax breaks for larger investments. This approach would be fiscally neutral, even increasing government revenue in the medium term.

Action 2

Financing via the stock market

An enterprise can also attract resources via the stock market, e.g. by issuing shares and bonds. By issuing publicly traded shares, the enterprise concurrently undertakes to publish detailed operating reports, in accordance with the legislation currently in force. To date, there have only been isolated instances of

Latvian businesses attracting financing by issuing shares on the stock market. One example worth mentioning is the emission of shares by SAF Tehnika in 2004.

An enterprise can also issue publicly traded bonds. Some Latvian enterprises have implemented this procedure successfully. In recent times, the most prominent example is Latvenergo, which has attracted funding worth EUR 180 million in this manner. The biggest volume of bonds, worth over EUR 640 million, has been issued by ABLV Bank. Bonds have also been issued by other banks such as Rietumu Bank, Baltic International Bank, as well as enterprises related to the pay-day loan sector. Bond issues are not common practice, because the related costs are quite high.

Attracting financing via the stock market is common practice in the United States and in other countries with developed stock markets. In recent years, steps have been taken in the European Union to encourage more active use of securities. For example, at the end of 2014, the European Central Bank launched a programme, under the auspices of which asset-backed securities are bought with the objective of diversifying sources of bank funds and stimulating the issue of new securities.5 This is an opportunity to stimulate the provision of credit to Latvia’s small and medium-sized enterprises.

In order to implement this, the so-called securitisation is used. Securitisation can take place in relation to a set credit portfolio, which the lender sells on to a specially established corporation that in turn, issues securities, which it sells to investors.6 Ordinarily, loans of a homogenous nature are chosen that make it easier to assess risk more accurately. As a result of securitisation, the issuer (emitter) of the securities attracts capital and gains a greater ability to obtain new loans. The credit risk as a result of this activity is passed to investors.

Combining securitisation with securities guaranteed with assets, makes it possible to securitize loans to small and medium-sized enterprises, concurrently also guaranteeing securities with the assets of these enterprises, reducing the risk posed to investors. This approach would make it possible to reduce the interest rates at which credit is available to small and medium-sized enterprises. In turn, securities could be sold to pension funds and other investors.

Action 3

Savings and loan associations

The availability of loans is also hindered by the lack of trust among lenders who believe that borrowers have opportunities not to repay debts, e.g. by means of insolvency proceedings. Moreover, the review of cases in courts is very slow. In recent years, Latvia’s commercial banks have tried to optimise their operations in Latvia’s regions, centralising decision-making. However, there is a solution that could ensure greater trust in borrowers among lenders. This is a regional savings and loan association model.

In many countries, savings and loan associations form an alternative network providing payment and financial services, based on the principles of collaboration and providing services that are important to the members of these companies. Usually, these have been formed as an alternative to the banking sector, but, over the course of time, in a number of countries they have secured an important place in the country’s financial system. For example, in the USA and Canada up to 40-50% of economically active citizens are members of savings and loan associations.7

Savings and loan associations have two potential advantages compared with commercial banks:

1) It would be much more difficult for borrowers in the regions to defraud savings and loan members, who are often their domestic or foreign neighbours;

2) When it comes to making a decision about whether or not to issue a loan, a savings and loan association is not only more likely to have a clearer impression of the borrower’s financial situation, but will probably also be knowledgeable vis-à-vis the specifics of commercial activity and development in the region in question.

The regulation of savings and loan associations is usually quite flexible, meaning that it is possible to establish them in cities or towns, or even among certain interest groups. For example, exiled Latvians formed several savings and loan associations in the United States and Canada after the Second World War, stimulating the circulation of money within the community.8

According to FCMC data, there were 32 saving and loan companies operating in Latvia at the end of the 1st quarter of 2015.9 Their total volume of assets and issued loans is negligible compared with other market players. The volume of assets held by savings and loan associations in Latvia at the end of the 2nd quarter of 2015 was EUR 24 million, while the volume of issued loans was only EUR 17.2 million. In comparison, in percentage terms, this is less than 0.1% of the total bank assets, which exceeded EUR 30 billion in 2015.

In Estonia and Lithuania, the development paths of savings and loan associations has varied. In Estonia, although there are over 20 savings and loan associations, their total volume of assets is small. In the middle of 2015, it amounted to slightly more than EUR 45 million. In recent years, the growth in the volume of assets has been quite rapid, but the distribution and significance of these associations in Estonia is small when compared with total bank assets (EUR 22 billion in the middle of 2015).

In Lithuania, savings and loan associations have developed significantly faster than in Estonia and Latvia. At the end of the first quarter of 2015, the total assets of Lithuania’s savings and loan associations amounted to about EUR 630 million or 2.8% of total bank assets. The network of savings and loan associations has been used to implement a “Business Development” project (an Investment and Guarantee Programme for certain target groups – young people aged up to 29 years of age, older people aged over 50 years of age, people out of work and people with disabilities). This approach could serve as one way in which to encourage the development of savings and loan associations, using the most important advantages of savings and loan associations – closer collaboration with members with a mutual interest in the attainment of joint goals.

Promoting the operation of savings and loan associations in Latvia would make a contribution to regional development, improving access to small loans that other lenders do not supply. The potential advantage of savings and loan associations could also be better knowledge of a borrower, who is simultaneously also a member of this association.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1

Profits reinvested by SMEs should not be subject to corporate income tax, retaining the existing accelerated depreciation model for large enterprises

Recommendation 2

Issue of asset-backed securities on the basis of SME loan portfolios:

- In collaboration with Altum and FCMC, the Ministry of Finance must establish a mechanism for buying loans that meet requirements from credit institutions;

- Using the ECB ABSPP programme, as well as the EIF guarantee programme, loans must be securitized and sold to the ECB under the auspices of this programme;

- The terms and conditions of financial securities companies must be changed, supporting the securitisation of SME loans so that they can be traded on the stock market or sold to investors.

Recommendation 3

Facilitate the development of savings and loans associations and their involvement in micro-lending in Latvia’s regions, involving municipalities and attracting financing from European Funds.

1 World Bank. 2015. Data bank.

2 CSB 2015, FCMC 2015. No data included about the real estate sector, because the decline in its volumes and trends after end of the lending boom would preclude adequate assessment of lending volumes and trends in other sectors.

3 Moreover, when companies were asked whether they had recently experienced a situation in which they required credit, but they did not apply for one, because they were concerned that the bank would reject their application, only 12% of SMEs, which did not apply for a loan, replied in the affirmative. The most affirmative answers to this question were made by micro-enterprises (17%). Bearing in mind the aforementioned factors, one can contend that 49% of all SIBiL SME respondents and 63% of the micro-enterprises surveyed were not interested in bank loans.

4 Eesti Statistika. 2015.

5 Asset-backed securities purchase programme (ABSPP).

6 Special purpose vehicle or SPV.

7 World Council of Credit Unions. 2014. Statistical Report.

http://www.woccu.org/documents/2014_Statistical_Report

8 E.g. the Latvian Heritage Federal Credit Union (USA).

http://www.latvianheritage.org/ and Latvian Credit Union (Canada) http://www.latviancreditunion.ca

9 FCMC. 2015.

10 Distribution calculated by dividing the number of members of savings and loan associations by the number of economically active citizens aged from 15 to 64 years.