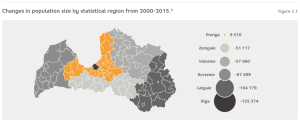

Depopulation is undoubtedly Latvia’s primary challenge. This most affects Latvia’s regions. In just the past decade, (2004-2014), the size of the Latvian population has declined by 12%. Future forecasts do not provide grounds for optimism. By 2025 the population will have declined by another 12%, reaching just 1.75 million. There will also be a significant change in population structure.1 The number of people of retirement age (>65 years) will increase by 4%, while the number of working age people will fall by 16%. The shrinking number of working-age people will face the rising burden of funding an increasing number of pensioners.

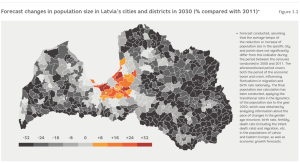

Latvia’s regions will be most seriously and directly hit by these changes. For the past 15 years, these regions, and Latgale in particular, have suffered the biggest fall in population (Figure 3.1). If this trend continues, it is forecast that in 2030, the population will decline by almost one third in most Latvian regions (Figure 3.2).1 The reduction in the number of people of working age will be even greater. How will the remaining inhabitants cover the costs of maintaining the regional infrastructure?

All too often, thinking about regional development has been dominated by a suburban mentality, particularly at the municipality level. Significant investments are made in schools, sports halls, cultural centres and similar infrastructure. However, comparatively little attention is paid to stimulating business and investments. In all likelihood, this attitude can be explained by the structure of incentives for municipalities. The main source of income for municipalities is the income-tax of residents declared according to their place of residence. Municipality revenues are not directly dependent on how many people work in the municipal territory.

We have analysed the economic side of the regional development equation. Good schools, kindergartens, sports centres and good roads are undeniably important components of life. However, people will not remain in places where they can’t hold down well-paid jobs. The viability of rural territories is currently based on three economic foundations: agriculture, forestry and logging, as well as rural tourism. These industries do not require a significant concentration of inhabitants. The development of rural territories is and will remain closely linked to the developmental trends of these industries. However, this offers no guarantee of jobs for all the inhabitants in the region.

The availability of jobs is one of the main factors in tying inhabitants to regions. One job created in a production plant creates three additional jobs related to the education of the labour force as well as the provision of other services. Thus the future existence and development of regional centres is closely related to the prospects for the development of manufacturing. Attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) to support manufacturing is key to creating jobs in Latvia’s regions. However, increased investment and a much more focused approach is required to attract foreign investors. The strategy of attracting investment for manufacturing must be built on three pillars: regional industrial zones, flexible professional education centres and a rapid response fund.

3.1. Industrial zones

Foreign direct investment is central to Latvia’s regional development. Empirical studies show that attracting large factories to specific territories can change territorial developmental trends. For example, if one compares territories which have succeeded in being chosen by a company as locations for manufacturing with territories that have also competed for this privilege but lost out, it is clear there was a significant increase in the value of real estate in the territories that attracted the FDI, which is an indirect indicator of a change in the level of welfare.3

The sustainable development of Latvia’s regions can be enhanced through the creation of industrial zones. The minimum components required for the establishment of a business/industrial zone are land, transport infrastructure, including access roads, water and sewerage, as well as both quantitative and qualitative labour force potential. The experience of both Latvia and other countries shows that the existence of industrial zones is an absolute prerequisite for attracting the interest of manufacturing investors.

Industrial zones in Latvia

Latvia has two successful examples of industrial zones: the Jelgava Industrial Zone and the Ventspils Industrial Zone, which has been developed by the Ventspils Free Port Authority in collaboration with Ventspils City Council (Figure 3.3).

The main factors that persuade foreign investors to invest in an industrial zone include transport and logistics infrastructure, telecommunications and IT infrastructure, the stability and transparency of the political, legal and legislative environment, the potential rise in the productivity of the company concerned, the skill level of the local labour force, labour force costs, and the size and nature of the national and regional market.

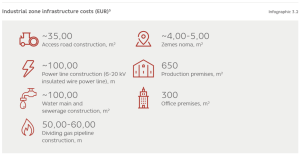

Industrial zones require significant investment (Infographic 3.2). Assuming that a new industrial zone were to be established with five production plants, each containing 2,000 m2 of manufacturing space and 750 m2 of office space, it would also be necessary to build a 1 km access road, 500 m power line, 500 m2 water main and sewerage systems and a 200 m dividing gas pipeline. It would also be necessary to pay a lease fee for the land spanning a total area of 5 ha. Accordingly, the total expenditures would come to approximately EUR 7.5 million. In turn, assuming that the infrastructure required for the industrial zone has been built (as is the case, for example, in Daugavpils and Valmiera), but that it is also necessary to build 4-5 production plants that incorporate 3,000 m2 of manufacturing space and office premises spanning an area of 1,000 m2, the total costs will also amount to approximately EUR 11 million.

Assuming the funding available for industrial zones currently amounts to approximately EUR 311 million, it would be possible to establish 4-5 new industrial zones in Latvia with the necessary infrastructure and 10 production plants with office premises.

Remaining funds, amounting to approximately EUR 80-90 million, could be used for the development of 6-7 smaller business/industrial zones, assuming that these already have the required basic infrastructure.

3.2. Industrial zone support system: employee training

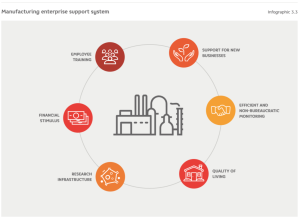

In order to attract manufacturing enterprises, countries and municipalities not only invest in physical infrastructure, but also provide an effective support system, offering various public benefits and forming an open collaboration platform for companies, local residents as well as state and municipal structures.

The various support system elements can be divided into six relative groups (Infographic 3.3). The quality of life and support for new businesses affect manufacturers indirectly, expanding the possibilities of finding the necessary workers and potential business partners. Other measures are aimed at reducing the manufacturing enterprise’s costs or increasing its productivity. Employee training, as well as efficient and non-bureaucratic monitoring are tasks that can also be resolved with limited finances.

Attracting foreign investors and local producers is one area in which the ability to respond quickly and flexibly to partners’ needs is particularly important. In order to ensure this, a rapid response fund should be set up, simultaneously combining the required authority, expertise and funding to resolve problems faced by manufacturers. This fund would, for example, train employees according to a companies specific requirements.

The majority of employees working for manufacturing enterprises need a professional education. This is the responsibility of the Ministry of Education and Science. By 2020 Latvia plans to increase the appeal of professional education and improve and expand collaboration with employers, involving them in the reform of the content of professional education and in the implementation of training, using an approach based on qualification practice and internships. In the spring of 2015, the Latvian parliament approved amendments to the Professional Education Law, which provide for the formation of councils comprised of industry experts. Their operation will be coordinated by the Confederation of Employers and will be comprised of representatives of employers, industry experts, employees, trade unions, the State and municipalities. Industry experts’ councils will be responsible for formulating the respective industry’s requirements (the required professions, specialisations and number of people to be trained), planning professional education programmes, as well as licensing and accreditation of professional education institutions and programmes.6 Since 2010 the Ministry of Education and Science has been optimising of professional education institutions, reducing their number and investing in the remaining bodies more intensively. Fifteen professional education competence centres have been established and are functioning.

Government policy is aimed at increasing the involvement of employers and the formation of a professional education system that allows them to find employees with the required qualifications in the labour market. However, several recent studies indicate that Latvian companies are not sufficiently active when it comes to implementing training in the workplace. Moreover, relatively few companies offer or plan to offer internships.7 In 2015, only one third of Latvian companies were prepared to offer internships and the proportion of such enterprises is actually declining. Some of the enterprises that offer internships do so in order to obtain cheap labour and do not invest in training.8 Thus while major reforms of the professional education system have been initiated, the system is not yet functioning effectively enough to provide employers with the employees they require.

Thus it is not certain that companies entering industrial zones will be able to find the employees they require without the involvement of proactive public players. Funding must be provided and a set of procedures should be drawn up to make it possible in a relatively short space of time – from the time of the decision to set up the production plant until the time it enters service – to train the employees a company requires.

3.3.External financing: EU funds

Regional development issues are an important issue at all levels of policy planning. The development of industrial zones conforms to current regional policy and funding availability from EU funds.

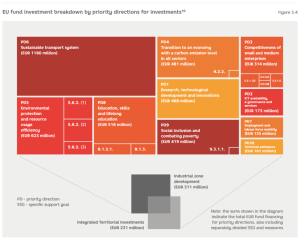

The EU fund investment action programme stipulates nine priority directions (PD) for investment, subordinate to each of which are several investment priorities with corresponding specific support goals (SSG) (Figure 3.4). Regional development and industrial zones are not divided into a separate priority direction for investment, but some investments are provided for certain administrative and functional territories, in addition to which, at the national level measures for individual territories have been highlighted as priorities, using project selection criteria.9

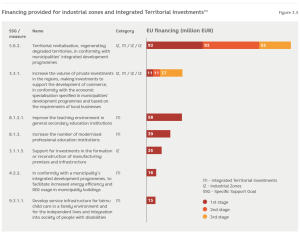

Accordingly, investments, which could be potentially allocated for the development of industrial zones, will have various preconditions (i.e. the territories, candidates, eligible costs and terms will vary) and will be managed by various government bodies, and, in securing them, recipients will have to consider not only the development of industrial zones, but also various target indicators more or less unrelated to industrial zones. For the development of industrial zones in particular, it will be possible to attract funds from measures that will be organised under three different measures. The Ministry of Environmental Protection and Regional Development plans to invest funds in the revitalisation of degraded territories and in the development of commerce. The recipients of these investments will be municipalities. The Ministry of Economics plans to facilitate the development of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) by supporting investments in manufacturing premises and infrastructure. The target group is enterprises. Total EU funding of EUR 311 million will be available under these measures (Figure 3.4 and Figure 3.5).

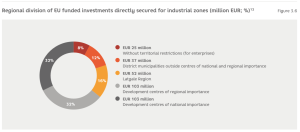

At least one third of the EU funding directly available for the development of industrial zones will be invested in development centres of national and regional significance (EUR 103 million) in each group of municipalities. At least 12% of EUR 37 million (see Figure 3.6) should be allocated to territories outside development centres of national and regional significance. Moreover, investments in each group of municipalities will most likely be proportionally divided up between the relevant municipalities.

The action programme envisages investment in developing centres of national significance, using Integrated Territorial Investments (ITI), combining investments from various measures within certain territories. In addition to both measures overseen by the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Regional Development, the financing of which can be allocated to the development of industrial zones, the ITI approach can also be used for investments in secondary education, professional education, increasing energy efficiency and in the deinstitutionalisation of children and people with disabilities – with the help of ITIs, investing a total of EUR 231 million (see Figure 3.5 and Figure 3.6). ITIs will be made in accordance with the integrated development programmes for development centres of national significance, with the managing institution concluding a delegation agreement with municipalities and municipalities themselves selecting projects. To a certain extent, ITIs point to additional investments that can be most easily attained, which could be used to ensure the efficient operation of industrial zones, but investments can also be combined using financing available under other measures.

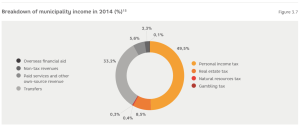

3.4. Local sources of financing: personal income tax

The most important source of income for municipalities is personal income tax (Figure 3.7). In compiling the state budget, planned personal income tax payments are divided between municipality and state budgets (for the past four years, the proportion has been 80%:20%), and the share allocated to municipalities is deposited into the budget of the municipality in which the taxpayer has declared his place of residence.13 Accordingly, municipalities benefit if inhabitants with high incomes declare their place of residence within their territory. In contrast, companies only have an indirect influence on the income of municipalities – via the employees of the company. However, once again here it is the employee’s declared place of residence that counts and not their place of work. The choice in favour of taxpayers’ place of residence as the criterion for division would not be so important if the majority of inhabitants lived and worked in the same municipality. Unfortunately, Latvia’s territorial structure is extremely fragmented, and data regarding personal income tax payment flows indicates that the majority of development centres of national importance provide jobs for inhabitants from surrounding municipalities.14

The autonomous functions of municipalities incorporate the provision of services that are oriented towards both inhabitants and enterprises, including providing support for commercial operations in general.16 However, financing available for the performance of these functions is always limited, and under the current system, in order to provide funds to implement this task, municipalities must firstly consider how to attract residents, meaning that the interests of enterprises are of secondary importance. This situation is not optimal.

As far as municipalities and their residents are concerned, collaboration with enterprises that will increase a territory’s economic activity in the long-term and provide new jobs could take precedence over the short-term interests of individual residents. Therefore, there should be stimuli allowing municipalities to utilise collaboration opportunities without forfeiting available funding. One means of achieving this would be to divide personal income tax payments between municipalities not only on the basis of taxpayers’ declared residency, but also on declared workplace.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1 – Industrial zones

Industrial zones will ensure sustainable regional development by attracting overseas investments and creating new jobs. The eventual number, location and costs of such industrial zones will depend on the quality of the infrastructure in regional centres. However, in all probability, the number of possible industrial zones will be quite small. For example, based on EU funds totalling EUR 311 million that will eventually be available for the development of industrial zones, it would be possible to establish 5-6 industrial zones that incorporate construction of the required infrastructure, i.e. access roads, water and sewerage systems, energy systems, telecommunications, as well as 10 production facilities including office premises. EU funds would also provide for the development of 6-7 industrial zones, where the basic infrastructure is already in place with the exception of production plants and office premises, which would still need to be built.

Recommendation 2 – Establishment of a rapid response fund

A rapid response fund should be established in order to able to respond quickly and flexibly to the requirements of potential foreign investors and enterprises interested in developing manufacturing facilities. It should possess the required authority, expertise and funding to resolve the problems facing manufacturers. This fund could, for example, be used to train employees. The fund should involve several state, municipal and non-governmental bodies, meaning that they would have to mutually collaborate and, moreover, do so within a limited timeframe. In order to ensure that the process progresses smoothly, one of the parties involved – preferably that which is the direct collaboration partner of the potential manufacturer – should manage the process. The objective of the process would be to provide interested enterprises with employees, while the solutions could vary in specific instances. Firstly, it should be verified whether it is possible to train employees in Latvia’s professional education system, i.e. by recruiting those already studying at the given moment or alternatively by attracting new students. The age of some of these trainees could differ from the average age of the young people acquiring a professional education. Therefore, the recruiting process should not be subject to any formal or informal age restrictions. It is possible that changes to professional education programmes will be required in order to satisfy the needs of investors. The system should be such that these changes can be implemented quite quickly and so that, parallel to this, the training of the next set of employees can begin. Regional high schools, as well as professional education institutions, could also be involved in the training process.

A mechanism enabling collaboration of education institutions at various levels needs to be established. Secondly, mastery of some of the required skills and proficiencies will often only be possible courtesy of job training provided by enterprises offering internships. Thus, if necessary, it must be possible for students to undertake internships with parent enterprises outside Latvia. Thirdly, parallel to the training process, consideration must also be given to opportunities to find employees not only in the domestic, but particularly in the EU job market, by focusing on the Latvian diaspora overseas and utilising re-emigration support measures. Finally, one should remember that public players engage in the provision of education services in the interests of society. Therefore, steps should firstly be taken to ensure that skills obtained as a result of state-funded job training can also be used in working for other enterprises in the industry. Secondly, in the event that trained employees choose to leave the Latvian job market in the long-run, a mechanism should be established so that the state can recover its investment.

Recommendation 3 – Partial linking of personal income tax to the workplace

In order to increase the incentive of municipalities to collaborate with business and thus facilitate the development of commerce in their territories, we propose that a portion of personal income tax payments should be allocated to those municipalities in which taxpayers’ workplaces are located. The portion of payments to be allocated could initially be small, but could subsequently increase. It is vital to create the system so as to minimise the administrative costs arising from these changes and so that the benefits from collaboration between municipalities and enterprises exceed the resultant costs. Disclosure of the workplaces where employees work could be voluntary. Thus, municipalities would have incentives to provide enterprises already operating in their territory, as well as potential newcomers, with services whose quality could induce these businesses to disclose their employees. However, the choice of whether or not to disclose the relevant information should be left to the enterprises concerned. These enterprises would then be in a position to assess whether the benefits from improvements in the quality of municipal services justify the additional administrative costs involved in disclosing their employees. Workplace declarations would only be possible in places where an enterprise has registered property, a representative office or branch. It would be also prudent to be set a minimum term during which an employee has to work at the specific company (e.g. one month) to preclude the possibility of a declaration being made for short-term employment relationships.

Finally, a control mechanism, introduced to dissuade companies from declaring fictional employees, could partially be made accessible to inhabitants who, via a uniform electronic system (e.g. the website latvija.lv), would have access to information about where their employer has declared their workplace. In addition, this mechanism would provide the opportunity to dispute or change this information.

1 Map publishing company Jāņa sēta and Grupa 93. 2014. “Public individual service offering assessment compared to population distribution”. 1st interim report. Characterisation and forecasts of demographic changes, Riga: MoEPRD.

2 Central Statistical Bureau. 2015.

3 Greenstone, M., & Moretti, E. 2004. Bidding for Industrial Plants: Does Winning a ‘Million Dollar Plant’ Increase Welfare? NBER Working Paper No. 9844.

4 Zimin, D. 2014. Kirde-Eesti, Estonia: Patterns of Socio-Economic Development – Case Study Report. GRINCOH Working Paper Series.

5 Calculations made by the authors, based on focus group interviews with representatives of Bucher Municipal and Ventspils Free Port Authority, as well as on information available from the homepages of Latvijas Gāze and Latvenergo.

6 Professional Education Law, “Latvias Vēstnesis” [The Official Gazette of the Government of Latvia], 213/215 (1637/1675) (10 June 1999).

7 AC Konsultācijas. 2015. “On the motivation of employers to engage in the introduction of work environment-based training”. Integrated Report”, Riga: LR Ministry of Economics.

8 Employers’ Confederation of Latvia (ECL. (2015). A study of the availability and quality of internships in Latvia. Concluding report. Riga: ECL.

9 LR Ministry of Finance. 2014. Action programme “Growth and Employment”. Riga: LR Ministry of Finance and LR Ministry of Finance. 2015. Supplement to the action programme “Growth and Employment”. Riga: LR Ministry of Finance.

10 LR Ministry of Finance. 2015.

11 LR Ministry of Finance.

12 LR Ministry of Finance. 2015.

13 LR Law “On Personal Income Tax”, “Latvijas Vēstnesis” [The Official Gazette of the Government of Latvia], 32. 1 June 1993.

14 Excolo Latvia. 2013. “Determination and analysis of the area of influence of development centres. Description of the development of planning regions, cities of the republic and district municipalities”. Concluding report of the study. Riga: SRDA.

15 The Treasury. 2015.

16 LR Law “On Local Governments”, “Latvijas Vēstnesis” [The Official Gazette of the Government of Latvia], 61 (192). 24 May 1994.