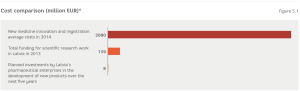

In 2012, the volume of the global pharmaceutical market reached $965 billion. It is forecast that it could reach $1200 billion by 2017.1 However, the pharmaceutical industry is characterised by very high research and development costs. Forecasts by pharmaceutical companies show that the discovery of new medicines and the receipt of registrations needed to authorise manufacturing costs over EUR 2 billion.2 These expenses make it clear that Latvia is a small player on the global market (Figure 5.1). However, the industry does have the potential to successful operate in various niche segments of the market.

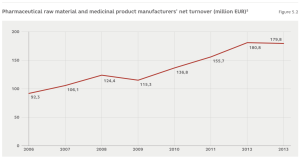

The direct contribution made by the manufacturing of pharmaceuticals to the added value of the Latvian economy amounts to approximately 0.5% of GDP or EUR 96 million (2012 data). Similarly to other industries, the pharmaceutical industry also has an indirect impact on added value in related sectors. Calculations show that this is how products and services worth another EUR 60 million are created.3 In 2013, there were 27 enterprises operating in the industry, which employed just over 2,000 employees.The average industry salary was EUR 1,075, which is 150% of the average salary within the economy. After the 2008-2010 crisis, the sector was characterised by stable growth, although turnover fell in 2013 (Figure 5.2). Provisional data from the State Agency of Medicines (SAM) shows that in 2014 the sales volumes of domestic pharmaceutical manufacturers continued to fall, declining by another 9%.

The turnover of the two biggest companies in the industry: Grindex and Olainfarm make up over 90% of the industry’s total turnover. Moreover, Olainfarm fully owns the third largest domestic pharmaceutical enterprise Silvanols. The three most important players in the industry are based in Riga (Grindex and the Institute of Organic Synthesis (OSI)) and Olaine (Olainfarm), and the whole industry is concentrated within the territory of Riga. (Figure 5.3)

5.1. Industry challenges

Research and new products

The pharmaceutical industry is one of the industries that most heavily invests in research. Research costs have risen sharply over the last half-century. Between 2001 and 2011, the annual research costs of 500 of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies more than doubled, reaching $131 billion.6

Empirical data shows that international collaboration networks are dominated by national clusters. For example, the Danish pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk primarily collaborates with Danish universities and institutes, while the American company Eli Lilly mainly works with American researchers. There are individual research institutes, whose operations are genuinely international and which collaborate with most of the major pharmaceutical companies. However, national research systems are formed around companies, not research institutes.7

In recent years, the big pharmaceutical companies have closed many research institutes, reduced investment in the initial phases of research and have ceased clinical field work (recruitment, data collection and so on) instead giving precedence to outsourcing.8 This trend creates opportunities for Latvia’s research institutions (and the internationally renowned OSI in particular). Although, given the significant research costs, it could well be too expensive for these institutions to provide the full process of developing, testing and registering new medicines, they do have the opportunity to become a part of international networks, carrying out specific tasks or using services provided by external service providers.

Clinical studies

Entrusting the performance of clinical studies to external service providers is another development that has affected the pharmaceutical industry in recent years.9 Central and Eastern European countries have experienced a boom in the volume of clinical studies. In some countries, (such as the Czech Republic) the volume of studies has almost reached the intensity level of leading countries in the field.10

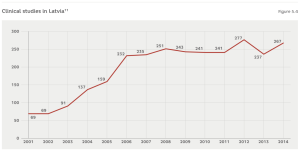

In Latvia, permits to conduct clinical studies are issued by the SAM. Last year, SAM issued permits for 53 clinical studies, while a total of 267 studies were conducted in Latvia. As Figure 5.4 shows, the number of studies is on the increase. These are mainly financed by foreign pharmaceutical companies and organised by foreign contractual research bodies (Amber CRO, Quintiles, etc.) authorised to conduct the relevant research by the aforementioned companies. The biggest clinical study centres are located at the Stradiņš Clinical University Hospital (where 29 studies were conducted in 2014) and the Riga Eastern Clinical University Hospital (21), while overall clinical studies were conducted by another 75 clinical study centres.

Overall, the organisation of clinical studies is an important element of the pharmaceutical business. However, it should be noted that Latvia is involved at the bottom of the industry’s supply chain – at the patient and hospital level.

Manufacturing and generic medicines

The world’s leading companies increasingly entrust the production of pharmaceutical products to business partners. External service providers mainly concentrate on the production of active pharmaceutical substances and leasing out certified production plants that meet international standards for the manufacture of other companies’ products, but they are also increasingly engaged in activities that increase added value such as manufacturing process development, design creation and the preparation of registration documentation. Manufacturing contractual organisations produce approximately one third of the total volume of products in the pharmaceutical industry.12

Entrusting manufacturing to business partners is closely linked to the production of patent-free or generic medicines. Their manufacturing volumes and total sales grow annually. In 2012, the generic medicine market amounted to 27% of the global market and had a value of $260 billion. By 2017, it is forecast that the market share of generic medicines will rise to 36% and will already be worth $432 billion.13

The value of the market share of generic medicines will increase, because the patents of a large number of original medicines have already expired or will do so in the next five years. In 2014, the 13 biggest pharmaceutical companies lost their patent rights to pharmaceuticals that generated over one third of these companies’ total turnover in 2013. The value of these medicines that can potentially be copied was greater than the whole US generic medicine market in 2013. (Figure 5.5)

An important part of the Latvian pharmaceutical business is comprised of the production of generic medicines and active pharmaceutical substances. Changes in the pharmaceutical market open up various opportunities for development. Overall, it appears that specialisation in the development and manufacturing process increases efficiency. However, specialisation also creates greater or lesser profitability in the overall value generation chain. Latvia’s pharmaceutical industry mainly responds to changes as opposed to controlling and choosing which position to occupy on this value generation chain.

Human resources

One of the most significant obstacles restricting development is the acute shortage of qualified personnel.

As a result of the demographic crisis, there are fewer students and it is likely that in future their number will decline even further. In turn, those currently working in the industry are aging as well as emigrating, in order to benefit from the international circulation of knowledge and to ensure their professional development. Another problem facing the industry is posed by the quality of the education obtained by young professionals.15

Registration of medicines

As an EU member state, registration of medicines takes place under the auspices of the joint system run by the medicinal product agencies of European countries (SAM is the Latvian agency). However, the domestic pharmaceuticals industry is not satisfied with the amount of time that it takes to register medicines whichsometimes significantly exceeds the timeframes stipulated in legislation. Another significant problem is the lack of a good partnership between the industry and the SAM. Manufacturers complain about the lack of support from the SAM and the low quality of its work. SAM, in turn, accuses producers of submitting documentation whose poor quality is such that it sometimes lengthens the registration time. However, everyone within the industry agress that the SAM can become a serious industry collaboration partner and that raising the capacity of the SAM could serve to facilitate the development of the whole industry. However, a change in attitudes by SAM is required.

SAM needs to develop a scientific advice service that would incorporate scientific consultations and assistance in the fulfilment of various procedures related to the registration of medicines. SAM could also assist in the development of the design of clinical and bio-equivalence studies for medicines, selections of methods and tests during the pre-clinical and clinical research process, as well as in the preparation of registration documentation and other matters. However, it is vital to ensure that SAM does not find itself in a conflict of interests, simultaneously drawing up and assessing registration documentation for medicines. It is possible that a scientific advice service could largely be provided as an external facility in collaboration with experts from local higher education institutions.

Market diversification

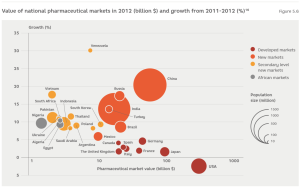

The biggest consumers of pharmaceutical products are developed countries. However, anticipated future growth is low (represented in Figure 5.6 by the dark red circles). In turn, a number of developing market economies have the most significant growth potential (represented in Figure 5.6 by orange circles). Secondary level new markets include various countries, which also have the potential to become important medicine markets, based on the size of their populations or the tempo of recent growth (represented in Figure 5.6 by – yellow circles). Finally, African markets, have high population sizes but low consumption of medicines (represented in Figure 5.6 by – grey circles).16

Developed markets are well-structured and foreseeable. In contrast, new markets are more complicated and differ, not only at national, but also at regional, urban and rural level.18 Additional difficulties are posed by the barriers to entry of many new markets, whereby foreign pharmaceutical companies are only allowed to distribute their products if they make direct investments and begin domestic production.19 Under such conditions, the first strategic choice of small and medium-sized pharmaceutical enterprises is whether or not to attract a business partner or to try to enter the market alone.20

Latvia’s pharmaceutical sector is largely geared towards exports, therefore, the development of foreign markets is particularly important. The most significant sales markets are Russia and the other CIS countries. In 2014, Olainfarm exported over two thirds of its products to CIS countries, while Grindex sold 76% of its ready medicines in CIS countries.21 Other important export markets for Latvia’s pharmaceutical companies are those in the neighbouring Baltic states and other EU members. In contrast, Latvian enterprises make minimal exports not only to the USA, which is the biggest market in terms of the consumption of medicines, but also to the emerging markets of China and India.

The unfavourable geopolitical situation in Russia and Ukraine and the decline in the value of their respective currencies are the main reasons for 2014’s slump in financial indicators. It is clear that market diversification is one of the sector’s main challenges. The industry’s development strategy envisages the implementation of measures aimed at increasing sales volumes in newly emerging markets in Asia and the Middle East, utilising enterprises’ knowledge of emerging markets in CIS countries and increasing the proportion of new emerging markets to 50%.22

Recommendations

Recommendation 1 – PharmaHub: collaboration, specialisation and niche products

Latvia’s pharmaceutical enterprises operate at various stages of the product value chain – in the development of original medicines, in clinical studies, in the production of active pharmaceutical substances and pharmaceutical products, and in the development of generic medicines and so on. In all probability, the industry is not currently ready to take control of the whole value generation chain. However, in many specialised directions, it would be worth trying to switch to niches generating higher added value. These opportunities must be taken through networking and utilising the know-how and advantages offered by partners. In order to ensure networking opportunities using the OSI platform, it is necessary to establish a joint usable technology transfer infrastructure in the form of a Pharma Hub, including a ready medicinal product form laboratory and pilot production plant. Estimates indicate that by investing EUR 8-12 million in the establishment of a PharmaHub, it would be possible to create a system in which both existing players and potential start-ups not only have the opportunity to discover new active pharmaceutical substances, but also to develop new forms of ready medicines.

Recommendation 2 – The State as a collaboration partner

The pharmaceutical market is global and characterised by a high level of competition. It is an environment in which private enterprises as well as national institutions and innovation systems often compete. Latvia’s pharmaceutical enterprises have set themselves the goal of developing their abilities to create, certify and launch the production of new generic medicines within three years and to increase their sales volumes in new emerging markets in Asia and the Middle East. In order for them to succeed, the capacity of the SAM must be significantly expanded by:

- developing a scientific advice function;

- ensuring the competence of SAM within the operating fields of Latvia’s pharmaceutical enterprises;

- facilitating the utilisation of SAM as a reference country within the EU’s decentralised registration procedure;

- concluding new bilateral agreements regarding the mutual recognition of pharmaceutical registrations outside the EU.

SAM requires EUR 600,000 of EU funding to establish a functioning scientific advice service and to recruit 12-18 freelance experts. Moreover, in order to ensure the availability of experts and to raise their skills, it is necessary to develop and expand clinical pharmaceutical programmes at Latvia’s higher education institutions.

Recommendation 3 – Human resources

In order to provide Latvia’s pharmaceutical enterprises with the human resources they require, the industry itself must be more proactive in taking responsibility for training young scientists. However, it is difficult to do this without a good basic infrastructure. A higher education industrial pharmaceutical programme should be developed, providing funding for at least 30 study places and supporting the recruitment of international scholar. In turn, in the realm of professional education, the pharmaceutical industry does not have its own professional education competence centre. Therefore, investments must be made in the Olaine College of Mechanics and Technology, establishing it as an industry centre of excellence.

Recommendation 4 – Market diversification

Support must be provided for the industry’s efforts to diversify and restructure product sales and distribution to (i) European Union countries, in particular emphasising Western European and Balkan countries (Bosnia and Herzegovina and Turkey, etc.); (ii) the Asia region with an emphasis on South-East Asia (Vietnam, Indonesia and the Philippines, etc.); and (iii) the Middle East (Egypt and Tunisia, etc.).

1 IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. 2013. The Global Use of Medicines: Outlook through 2017. Parsippany, NJ: IMS.

2 Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development (CSDD). 2014. Cost of developing a new drug. Boston, Mass.: CSDD.

3 Aprēķiniem izmantoti multiplikatori no PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC). 2013. The pharmaceutical industry’s contribution to the Latvian economy. Riga: PwC.

4 CSB, CSDD 2014, ALCPI 2015.

5 CSB. 2015.

6 A.T. Kearny. (2013). Unleashing Pharma from the R&D Value Chain. Chicago, Il: A.T. Kearny.

7 Rafols, I., Hopkins, M. M., Hoekman, J., Siepel, J., O’Hare, A., Perianes-Rodriguez, A., & Nightingale, P. (2014). Big Pharma, little science? A bibliometric perspective on Big Pharma’s R&D decline. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 81, 22-38.

8 Hirschler, B., & Kelland, K. (2010). Big Pharma, Small R&D. London: Reuters.

9 Petryna, A. (2009). When Experiments Travel: Clinical Trials and the Global Search for Human Subjects. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

10 Thiers, F. A., Sinskey, A. J., & Berndt, E. R. (2008). Trends in the globalisation of clinical trials. Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery, 7(1), 13-14.

11 State Agency of Medicines.

12 CEPTON Strategies. 2008. Strategic outsourcing across the pharmaceuticals value chain. Munchen: CEPTON.

13 IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. 2013. The Global Use of Medicines: Outlook through 2017. Parsippany, NJ: IMS.

14 Munos, 2015

15 The Association of the Latvian Chemical and Pharmaceutical Industry (ALCPI). (2015). The Latvian chemical and pharmaceutical industry’s innovative growth strategy. Riga: ALCPI.

16 The markets in Russia and Ukraine so important to Latvian companies have declined since 2012.

17 Booz & Company. 2013.

18 Yadav, P., & Smith, L. 2014. Pharmaceutical Company Strategies and Distribution Systems in Emerging Markets. In A. J. Culyer, Encyclopedia of Health Economics (Vol. 3, pp. 1-8). San Diego: Elsevier.

19 World Economic Forum (WEF). 2013. Enabling Trade. Valuing Growth Opportunities. Geneva: WEF.

20 Quintiles. 2015. Emerging markets: Four entry strategies for small and midsized companies. Durham, NC: Quintiles.

21 Grindex. 2015 2014 Book. Riga: Grindex and Olainfarm. 2015. AS “Olainfarm” 2014 Consolidated Annual Report and Conglomerate Parent Company Annual Report. Olaine: Olainfarm.

22 The Association of the Latvian Chemical and Pharmaceutical Industry (ALCPI). (2015). The Latvian chemical and pharmaceutical industry’s innovative growth strategy. Riga: ALCPI.